M&Ms: Projections

Why future projects and estimates are useless in business in the 108th edition.

It gets hot in the concrete jungle during the summer.

And that summer in the early 2000s, you saw the water evaporating from the street. My boss and I sat in bumper-to-bumper traffic inside a hot rented van on the I-87 merging onto FDR Drive.

We headed downtown, NYC, to take risk and do manual labor.

My boss then, Enzo, had a very successful restaurant business, but he was seduced downtown by the siren song of scalable cash flow. He had become convinced that scalable boring businesses were the way to go. Being pragmatic and smart, a graduate of a top U.S. school, he decided to go the simplest and what he thought was the surest path to big money. A Donut Franchise. You know, the ones selling donuts, breakfast items, coffee, etc.

The donut franchise's corporate office sent people with laptops, spreadsheets, and projections to meet with Enzo. Given his extensive food experience and a successful fine-dining restaurant, they were sure it would work.

They had convinced him to bet big.

And that day, he and I were on our way to add the finishing touches to the donut shop in NYC. When we finally got downtown on that sweating bullets day, we were greeted with more traffic.

We discussed the projections and the spreadsheets they'd shown him the whole way.

Instead of one small donut franchise to test the waters, he would try multiple bigger ones. And one of them would be in the middle of the greatest and most expensive cities on earth, New York City. The corporate donut guys were convinced; you can't get more foot traffic than that. The numbers on the laptop looked huge.

My boss was a risk taker, but until then, every risk was relatively small and scaled slowly. Enzo tried many things when he decided to chase entrepreneurship instead of going into corporate law. He opened up a pastry shop that worked out well. He then opened up a coffee shop that worked out well too.

Then Enzo took money from those bets and opened a small restaurant. When he opened that restaurant, he had no projections. He was just someone placing a bet based on gut feelings. That restaurant worked out incredibly well; he then added to it and made it bigger and bigger, and that worked too. But each addition was in phases. It seemed to me, just a 17-year-old kid back then, that it was easier and safer to take something that was working well and add to it.

But this donut bet was different; he had never bet as big as these franchises before.

While in the van, downtown, near Wall St., at a red light, we saw an attractive, professionally dressed woman with a briefcase. She was probably in her 40s. Then out of nowhere, Enzo calls out to her. She ignored him, but he shouted, "Hey, baby! Looking good! Why don't you come here and talk stocks, bonds, and dividends to me? I am into all that stuff." It was probably the worst pickup line ever, and given he was married, I am certain he did not intend to pick anyone up. But it was a good line to get a reaction from a bored 17-year-old kid in the van on a hot day, me. At the time, I thought, "The balls on this guy Enzo."

The donut franchises opened, and within a few months, they all failed.

Enzo was smart enough to cut his losses fast. But those donut shops made money evaporate faster than the sun removed moisture from the pavement on those New York City summer streets. What happened in a few months would take him a couple of years to recover. But it could've been worse; he could've put even more good money after bad.

Most restaurant owners work hard. But Enzo, born of Calabrese immigrants, didn't just work hard; he was also brilliant. In fact, with a 3.9 GPA from a top school, "without trying too hard," he said, he was one of the smartest people I ever worked for. He would've run laps around most of the people I later worked with in corporate America. Eventually, he not only recovered but he went on to open several other very successful restaurants.

And yet, there he was back then, intoxicated by those spreadsheet projections.

But this all highlights something important for the rest of us. Nothing is more intoxicating than a spreadsheet showing revenue into the future as if it will for sure occur or keep recurring.

Even Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger had to learn this lesson hard. To the point where Warren Buffet took the stance of

"I have no use whatsoever for projections or forecasts. They create an illusion of apparent precision. The more meticulous they are, the more concerned you should be. We never look at projections, but we care very much about and look very deeply at track records. If a company has a lousy track record but a 'very bright future,' we will miss the opportunity to buy it."

—Warren Buffet.

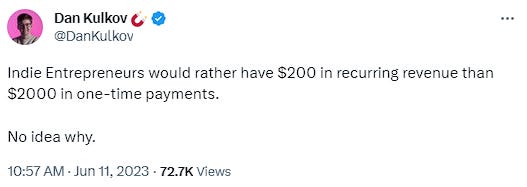

To understand how intoxicating prediction can be, you just need to look at all the Indie Hackers willing to take $200 dollars in recurring revenue rather than $2,000 in one-time payments. Just so they can have “predictable” projections.

Daniel posed the question here, and many people say they will take the $10 dollars a month.

"There is nothing wrong about guessing in business unless you call it 'estimating' and attach some undue importance to it. I want to know when I am guessing and when I am dealing with facts."

—Harvey Firestone, Men, and Rubber: The Story of Business.

Enzo taught me many business lessons I'll never forget.

But this is a big one that I hope I don't have to repeat.

No future projections are certain in business, not even "pretty much guaranteed boring cash flow," as the corporate franchise owners put it back then to Enzo. Not even SaaS subscriptions projected into the future are safe; they have churn too.

A Few Great Newsletters

I wanted to highlight a few newsletters I think are worth reading from folks taking our newsletter cohort through Small Bets this go-round.

There are too many great ones for me to feature here, but I thought I would pick a few and share them with you.

The Monstery of Self writes some wonderful life lessons and insights from their journey through a career in tech.

Jordan writes some incredible insights for mid-level to senior engineers. Last week’s edition on not being blocked was a valuable set of things that ought to help any career engineer.

Tri is a co-founder and CTO of a YC-backed company. He writes on lessons from his journey, tech, and stoicism.

JD writes on lessons he’s internalized and applied from books. This week’s book is High Output Management by Andy Grove. And he touches on many other interesting things he comes across from his journey in management.

Danny writes about his learnings and growth journey on the internet. He has taken several courses, including Write of Passage, and is helping build some himself. And he shares all of his insights.

Mak is a great writer that also took Write of Passage; he writes lessons he learned, becoming a better learner, productivity, and mental models. Many of these touch on business, like this week’s edition

Mike writes on AI and he is already off to an incredible start with his first edition.

Two Memes: Rubbish, Safe

My cousin moved to the U.S. from the U.K, and we always enjoy his mastery of the English language.

Programmers are safe.

As always, thank you for reading.

-Louie

P.S. You can reply to this email; it will get to me, and I will read it even if I can’t always reply in a timely manner.

Loved the article as usual, Louie and thank you so much for the shout-out.

That really means a lot and it looks like it helped a lot. Looking forward to the cohort tonight!

Thanks for recommending SOAK, Louie.

I'm confident that I'm taking the first steps towards something meaningful and sustainable, and I wouldn't have been able to do it if it weren't for The Newsletter Launchpad .

You and Chris, and the entire Small Bets community, make all the difference. 🙏