M&Ms: Failed Dreams

My phone was going off that morning, iMessage after iMessage.

One read, "Great news, Louie, you're moving onto the next round. But we need to hurry. They're closing their series A and need you in there fast. Can you meet their whole engineering team today? They plan to drill you hard, so be ready!!"

Another read, "Louie, I've got bad news. It looks like they went with another candidate, someone more qualified at later stages to run their engineering teams. But that's okay. The team was probably too big for your liking anyway. I'll get on finding something earlier stage for you." Another from one of my old boss read, "I heard you're done playing entrepreneur. Text me back." An old colleague wrote, "Are you interested in a VP of engineering role? I think you'd be perfect. Good company, good founders."

Those and a stream of other text messages bombarded my phone that day as I headed into the city for an interview. All well-meaning from friends, recruiters, and acquaintances still in the industry, all trying to pick me back up on my feet. As a side note, I am grateful for my friends, former colleagues, and acquaintances and always will be.

But with my funds depleted and a family to feed, I had no choice but to get back on the job hunt. I had put the bat signal out, "Hey Team, things placing small bets aren't going well. I am out of money and need a job."

Unfortunately for me, this was no longer the same job market I left. Still, I had some small advantage. I could sense it in the interviews.

But I was failing a lot of these interviews. Engineering leadership interviews can be notoriously hard. But, also, my heart just wasn't in it.

I felt like a free slave who couldn't make it out on his own, reporting back to the plantation. To have the shackles of a two-plus-hour commute reinstated. To have my entire calendar re-filled with meetings and dictated to me again. To have 60 hours a week siphoned from the things I liked doing and working on. To have everything I produce on my own time requires permission again, maybe even this newsletter, who knows. And worse, I had to seem like I enjoyed all that to land a role.

In one of my failed interviews, the interviewer had asked, "Are you committed this time? Will you stick around?" While he twirled a pen and stared at my resume. Another wanted to know "if I regretted my decision to leave?" In my mind, I thought, "The only thing I regret is being back here interviewing."

But I couldn't say that. I had a family to feed.

Here, I was beaten in business. And I was begging for another chance at a sweet, sweet, high salary again. But the beatings weighed on me, and they impacted my performance in these interviews. I felt like a failure before these interviewers even walked into the room or joined the Zoom. And add to that the fact that I was being judged and thrown on a whiteboard even after all this experience, after all these projects.

Still, despite my abysmal performance in some of these interviews, a terrible market, I had this small advantage. I had real experience. My experience managing people came across well, and the fact that I never stopped writing code and all my online writing gave me a small edge. One interviewer even said, "I love your writing on Twitter. I've been following you for a while, and there is no question in my book that you are competent. But you'll have to stop writing on Twitter if you take this role. It's too risky."

But, still, all of that gave me enough of an advantage to make it to the second and third rounds for some of these well-paying jobs. But the final round for this role I was on the train to go interview for was something special. I had to meet the entire engineering team at once to get drilled.

Picture this: when I got to their office, I asked the front desk attendant if I could use the bathroom before I walked into the interview room. I went into the bathroom, splashed water on my face, slapped myself, and told myself, "You've been through worse than this. You've been jumped and beaten by an entire gang in The Bronx before. You've been robbed at gunpoint. You come from the very bottom. And you climbed your way up the gravel. Get your shit together, go in that room, crush this interview, and land this role. You got people depending on you."

Man, when I walked into that room, it was like a lion attempting to take over a new pride. You just knew there would be intellectual violence to be accepted in. But to be honest, I couldn't blame those people for all the tough questions. They asked me about scale, they asked me about my management principles and asked me to draw Kafka topics on a whiteboard. I was an unknown stranger, and they needed to test my mantle.

But when I walked out of there, and before I made it to The Metro North, I had the text from the recruiter, "I've got great news, Louie!!!! They Loved you. Will call you later with the official offer." The pride had accepted me.

The relief that my family would be okay and that my kids would get to eat well again quickly washed away because I still felt like a massive failure.

But my mother broke up my moping with a call on that train ride. She asked, "How did it go?" I told her, "Good, I guess they want to make me an offer." She said, "That's great news. I am glad you are getting a real job again. Now all our relatives can be proud again. We aren't meant to be entrepreneurs, Louie. Look at where we come from. But this is great. Your kids will learn from you that they've got to work hard and climb the ladder like you did." And she hung up. I know my mom loves me, and I love her very much, and in many ways, she projects her own fears in our conversations about entrepreneurship.

But my mother got me thinking of my kids, and as I thought of my kids, I remembered that this startup was clear: they needed me in the office. I thought, "No more walking my kids to school or picking them up," as I stared out The Metro North window toward Westchester, NY.

Then I woke up.

And I frantically checked my phone, sweating, but I had none of those messages. It all turned out to be one really bad dream, a nightmare really—my worst fears.

-- --

*By the way, even though tonight's story is fiction, everything in this story happened to me at some point in my past, including getting drilled by entire engineering teams in interviews and everything else.

This story is likely the worst case for me in the journey I am on. And this is probably a good exercise for you to think through your worst fears and what you want to avoid, too.

This story encompasses what I think would happen to me if I failed. In the worst case, it probably wouldn't be the end of the world. But you can bet that I am going to try my hardest not to fail.

Four Tweets: Imagine, Lifestyle, Working on Our Terms, 40 things

Since tonight’s piece is all about “imagining”, Naval had a great tweet that might help you interact with those around you. Maybe even with yourself.

Simon always has wonderful pictures of his lifestyle in New Hampshire.

You’ll often hear me talk about the advantages of working on your terms, which Simon definitely seems to do.

But working on your own terms isn’t about not working.

And this comment perfectly captures that. When you are doing work you love, you will do great work.

There was another great tweet today, “40 things Rockefeller wrote to his son”, that perfectly captures this.

Specifically number 39: “The person who can create value the most is the person who devotes himself completely to his favorite activities.”

Two Memes: Push Before Going, Disputed Endorsements

A meme to go with Naval’s tweet.

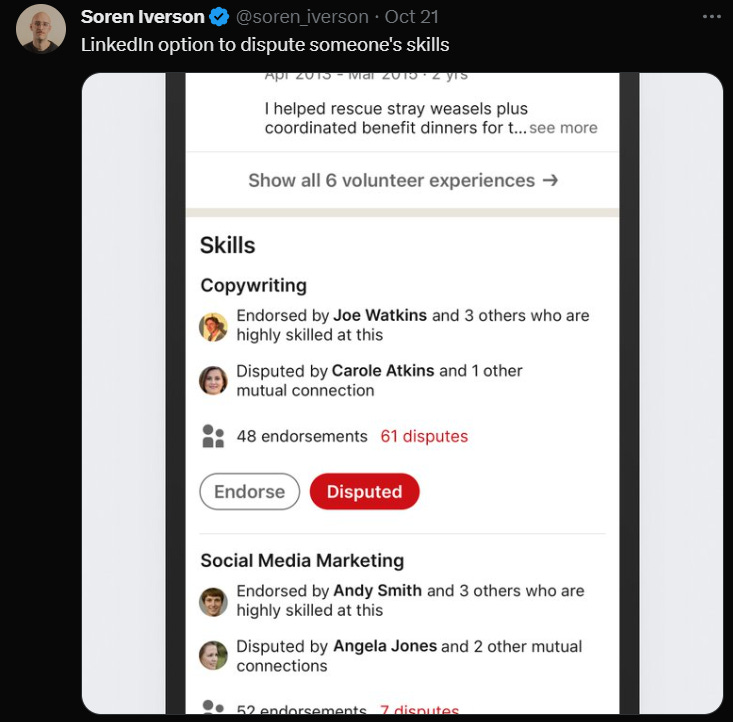

Can you imagine LinkedIn with the option to dispute skills?

—Louie

P.S. You can reply to this email; it will get to me, and I will read it.

you scared the shit out of me

ha ha, I kept reading and reading, thinking it was headed for a dream sequence, but the closer I got to the end I was thinking, damn, maybe he's really going back. good cliff hanger to the very end. glad for all of us that it was just a dream!