M&Ms: The Good Times Cannot Last

Diversify when things are good on the 105th edition.

There was a point in my life where I had the best job in the world, yet it did not last.

I felt incredibly lucky and still do for having had that experience. I was respected in my company. And friends respected me for having that kind of role and rising so fast inside the firm.

I was tinkering. I was building stuff. I was managing people. I was making important decisions. I had ownership. The job had everything I wanted and more.

I had teams of people reporting to me; when I shared internally, people would pay attention. The other teams, the product, and the business valued me. They roped me in for my opinion on every big feature.

If I wanted to, I could rogue an entire team to build something that was not on the prioritization list. Heck, I could send my team off to make something we'd just thought of that wasn't on ANY list. And I frequently did. I was not some lead-from-the-back kind of leader. I was on the front lines with my people; they trusted me, and I trusted them. I was managing and writing code at the same time. And no one would dare get mad at us publicly, even when we failed. And we failed many times.

But our failures didn't matter because it was glorious the few times things worked. Sales skyrocketed. My band of rebel software engineers and I were heroes when that happened. And all our sins were paid for in full and forgiven.

It was a wicked and wild time that gave rise to our firm—tons of "easy" Venture Dollars in the middle of the last decade, the low-interest rate phenomena. People rolled the dice on us with big money at stake. And we seemed determined to make the most of it, not just come close to it.

But the most gratifying thing was to have our "political enemies" in the firm sit on the sidelines and watch us rise. They'd see us not follow the set path, and they'd complain loudly in private. But word got back to us. And because whatever we were doing worked out, they'd have to sit on the stands at the all-hands and watch as we got promoted.

Once, I was called into a meeting where one of our "political enemies" complained about me and my teams. They said, "Louie, this place is a wild west, and you and your teams are a bunch of cowboys and cowgirls." And my response, without exaggeration, was, "You're damn right; it's the cowboys that have to tame the west." It felt good to see the anger in our political enemies' eyes.

You see, much like the Venture Capitalists who funded us or the founder who started the firm, we also rolled the dice. And the times that went our way paid for all the times that didn't.

It was a glorious job and a glorious time for me.

I had so much fun, and the firm succeeded, and we succeeded. In a short couple of years, we had over 10 million customers from zero, a billion in sales, and we got acquired for $3.3 billion.

And then the good times ended. One minute we had it all, and the next, the walls started to close on us.

In the startup game, you are damned if the startup you work for fails. But you, as an employee, are also damned if it succeeds.

Because success, whether by IPO or acquisition, means that the cowboys and cowgirls must stop riding, be reined in, and grow up. The firm has to mature like any living organism; as it grows, it has to get old.

But the firm as an organism is also made up of many little organisms, as most organisms usually are. Those little organisms in the firm are the teams, you, and your co-workers. And because of technology, firms are growing, aging, and dying much faster than they ever used to.

And so if the good times have to always come to an end for any firm, even the successful, it would make sense to prepare for a time when the good times have to end.

A wise person would use some of the surplus knowledge, credibility, reputation, and connections and pull some of it out outside the firm for themselves. I was not that wise back then; I had too much fun being king of my domain inside my firm.

I was a little wise, but I could’ve been much wiser.

I could have written a hell of a lot more about what I was doing. I could have improved my communication skills and proven them to the world. I could have carved a corner of the internet for myself. I could have demonstrated my coding skills by having a bigger public body of work. I could have built more things on the side for myself that had nothing to do with my firm. I could have built or acquired things that made money. I did some, but I could've done more. It’s always the things we could’ve done but didn’t that we regret.

Wise people always diversify, especially when things are good.

Take Charlie Munger, one of my heroes, who bought a firm called Blue Chip Stamps at a time when collecting stamps was cool. Stamps became a loyalty program that many firms used to reward their customers with. You got issued a stamp in proportion to your purchase back in the day. The business was at the top of the world at one point; it was doing so well it had an anti-trust case against it.

And while it was doing well, Charlie Munger and his partner Warren Buffet began to diversify like the wise people they are.

In 1970 Blue Chip Stamps had sales of $126 million. In 1972, Munger and Buffet used Blue Chip Stamps float to gain a controlling interest in See's Candies. Candy turned out to be a more timeless business than collectible stamps; who would’ve thought? Later they acquired one hundred percent of See's using funds from Blue Chip Stamps.

Buffet wrote, "When I was told that even certain brothels gave stamps to their patrons, I felt I had finally found a sure thing."

However, the good times cannot last.

Sales for Blue Chip Stamps dropped to $19.4 million in 1980 and $1.5 million in 1990. In 2006, revenues came in at $25,920.

But it didn't matter because Buffet and Munger were diversifying the entire time.

Since you know that bad things will happen, and now you know they happen faster, it's just a matter of when. You have an advantage; you can take action now. The good times cannot last; as creating firms from scratch and scaling companies gets easier, the firm's lifecycle will become shorter and shorter.

Pull some of your surplus credibility, reputation, capital, and relationships outside of work. Build more of that outside of the firm. Keep a written record of your accomplishments that exists for others to see outside of your job. Build up reusable assets. If you hate writing words, then write code. If you hate words and code, then do business and make money.

But do something.

A small ad from me:

We are preparing to run our 3-week live class on newsletters at the end of the month.

If you’ve thought about starting a newsletter and want to learn and get feedback from Chris and me, we would love to have you in there.

The class is through Small Bets; if you are already a small bets member, registration is open for our class here, free for all small bets members.

If you're not a Small Bets member, sign up for a Small Bets membership (a one-time lifetime price for the community right now), and you will get access to our live class and many others too.

Three Things: Compression is giving, Struggling for what you want, Legal ownership

What's fascinating about this email from Niraj to the CEO of Snapchat is not that it was a cold email but the response from Evan.

It reminds me of a saying by Benjamin Franklin, "Eat to please yourself, but dress to please others."

When you take the time to compress your writing, you aren't doing it for yourself; you’re doing it for other people. And some of them will appreciate it so much they may give you an internship or something precious you want because you didn't waste their time.

Here is another way to frame this, what if you wrote something that went viral? But in it you had a bunch of filler words, that are very common in corporate America.

Millions read your viral piece. But every extra word that wasn't necessary wastes a million humans' precious seconds in this life.

You don't spend time compressing well and writing well for yourself. You do it for other humans. You are giving to others by doing that. And some will notice and be grateful for it...

This thread surfacing this interaction between Jerry Seinfeld and a struggling comedian was incredible.

At the end of the story, Jerry said, “How do people live like that.”

And to me, it meant the ultimate lesson from that video is that living a life you want to be living, even if it is more of a struggle than doing the easy thing, is way more rewarding.

This piece by Taleb from 2016 is incredible.

It perfectly captures some of the fears I had and some of the unlearning I’ve had to do over the last few years.

A Tweet Thread from me this week:

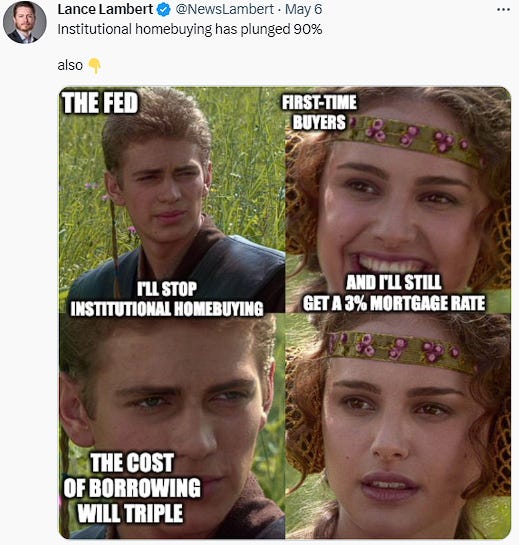

Three Memes: Deadlocks Explained, No More Institutional Home Buying, Back Breaking

A deadlock is a lot like a pistol duel. Who’s going to blink first?

At least the Fed solved one problem in rental properties. Blackstone won’t be buying up entire neighborhoods anymore. But we won’t be buying anything either.

That’s a nicely designed chair, but our backs are still breaking.

As always, thank you for reading.

-Louie

P.S. You can reply to this email; it will get to me, and I will read it even if I can’t always reply in a timely manner.

Oh God! I also wish I realized this during the good times.

A few years back I went viral (positively) in my country, even generated dozens of news article profile about me. A lot of my friends were suggesting me to create contents to capitalize on the momentum. And during the high-growth years that followed I also rarely shared anything publicly.

I thought it was silly and superficial to have a lot of followers. Little did I know that years later it can be a good business and a nice starting point to start one :")

Beautifully written piece Louie. I would say comparison is always not bad. It's very useful especially with a heads down kind of guy like me. It's actually helped me move up in my career. I really didn't care too much about going up the ladder. What really motivated me was:

- I would not get interesting stuff to work on

- Non-tech managers would decide how the work should be done.

- I would not be able to decide what go work on.

It's only when the green eyed monster gets involved that comparison are bad.